The End of The Era of Indifferent Capital

June 21, 2022

The next year will be challenging for startups. Promising companies will struggle. Many will fail. The only consolation is that the “era of indifferent capital” is coming to a close — may it never return.

What do I mean by “indifferent capital?”

Historically, VC was a boutique business where investors viewed themselves as mentors to their entrepreneur protégés. VCs were financially driven, but they also put considerable relationship capital to work in each startup.

In the old model, failures we also painful for the VC. They had their ego *and* cash tied up in a startup’s success. VCs weren’t always paragons of virtue. There were plenty of bad actors. But there was a sense of responsibility to truly support their startups.

Attitudes have changed over the last half-decade. Indifferent VCs got comfortable writing checks, sometimes quite large ones, with no desire for a board seat, no meaningful oversight rights or real involvement at all. They believe startups are born great, not built over time.

Indifferent VCs are speculators and see each startup as part of a portfolio of lottery tickets.

What’s the value of a single lottery ticket?

If it’s a winner, you’ll guard it with your life.

But if not a winner, it’s tossed in the trash without a second thought.

Investments are almost entirely transactional — pro-rata rights and liquidation preferences are important, but little else. Indifferent VCs will pay premium prices, but they’re thinking in bets. A failed company is a lost wager in a broader portfolio, and that’s all.

Indifferent VCs aren’t out to get you. They aren’t the stereotypical predatory “vulture capitalists.” They’re not hostile. Indifferent VCs just don’t care about anything except startups that show traction toward becoming a home run. They are happy to trash the rest.

The bull market hid the weaknesses of this model, and indifferent investors became popular with founders. But with the macro downturn, I think the weakness of this kind of capricious capital is about to become apparent.

Indifferent investors were stingy with support for startups that lacked massive markups in very short order. In the days ahead, I don’t see many of them writing support checks to struggling or even solid startups. Certainly, they won’t invest time to engineer soft landings.

Outsider VCs will have little appetite for salvaging startups with messy cap tables and sky-high valuations. Outside-led “Down rounds” won’t happen that often — a startup needs to be producing considerable revenue for new investors to be motivated to come in and clean up.

As a result, many startups are going to struggle to find capital inside or outside. I expect to receive a lot of calls from founders whose indifferent later-stage investors have stopped responding to emails or calls. We’re going to do everything we can to help them.

If you’re still in the early stages of your startup, pay close attention to how firms act over the next 6–12 months. Avoid VCs who will treat startups like a toss of the dice. Prioritize those who will put in the work and stick with you even when you roll snake eyes.

While this will be a difficult period, I believe it will also be a real period of strength for committed VCs and hopefully the end of the era of indifferent capital as we move toward a healthier VC model ahead.

On The Perils of Pricing to Perfection

October 3, 2021

These days I find myself talking with our founders often about the perils of pricing to perfection: Founders need to balance the desire to optimize in the short-term against potential long-term fundraising complications.

Imagine you are a “hot” early-stage startup and have $500K in ARR. VC’s are keen to invest and you get two offers:

A) $6M on $30M

B) $12M on $60M

Seems pretty obvious which one you should take, right?

You might ask, “Why would anyone choose anything other than B? You’re literally getting 2X more money for the same dilution?”

I call this kind of short-term optimization “pricing to perfection,” and while it is satisfying at the moment it creates many downstream problems.

E.g. If you raise the $12M round and burn the money growing ARR from $500K to $5M over the next two years, there’s a good chance your investors will be underwhelmed!

If you raised the $6M round, and make the same or even more modest progress, your VCs will likely be excited about the business and eager to put another round together.

Expectations management matters!

This is one of the hardest conversations I have with founders.

Taking less capital seems illogical. However, unless you can efficiently use the extra capital, the valuation premium comes with costs. Very few companies get twice the results from burning twice the capital.

Here’s what you stand to lose when you get an unrealistically high valuation:

⏱ ️More Money Does Not Equal More Time

More capital isn’t for more runway. They expect you to hire & burn the money in an 18–24 month timeframe in the hope that it accelerates your startup’s progress, and puts you in position to raise a much larger round.

The pressure to grow at all costs will be immense and you’ll be encouraged to spend on underperforming activities to boost growth. As a result, your burn rate will rise, giving you less time to respond to challenges in the market or to fix problems in your execution.

This post explains the dynamics involved in greater detail, but in short, high valuations will increase your stress levels and eliminate most of your margin for error — a costly tradeoff for excess capital you don’t yet know how you’ll use.

😢 You lose VC support

When founders can command high valuations it’s usually because their story-telling/reputation precedes their startup’s results. VCs believe they are investing in a rocketship. Slow progress shatters that illusion and creates discontent.

Think of the initial hypothetical from the investor’s perspective. They paid a premium price and are seeing disappointing performance. Is it surprising they are impatient with the founders and don’t want to continue funding an underperforming asset?

If you raise a smaller round and have solid results, there’s a good chance that goodwill & a revised narrative can unlock another round of funding from insiders. If you raise at a higher valuation, have a higher burn & not much better results, inside support will evaporate.

😍 You lose the VC you want

If you’re optimizing for price, you’re getting the investor who was willing to pay the most and that’s seldom the investor you really want to work with — this is short-sighted optimization that often proves irresistible.

🚪 You lose exit options

Imagine after two years you get an offer to buy your company for $100M and you think it’s a good idea.

If you chose option A, you’d stand to make tens of millions of dollars!

If you chose option B, your VCs wouldn’t likely support the deal.

Founders tend to have big dreams at the early-stage, but running a startup is *really* hard and you may appreciate the exit optionality earlier than you think. Don’t give it away casually.

Startup failure is less frequently the result of bad product decisions or poor financial management. In most cases, what separates failure from success is an extra year or two to get product/market fit or go-to-market dialed in. More capital makes this harder, not easier.

Valuation metrics are extremely generous right now, but they are still primarily driven over time by user/revenue growth. Building metrics that keep up with sky-high valuations is incredibly difficult.

Benjamin Graham famously said “In the short run, the market is a voting machine but in the long run, it is a weighing machine.” This is ultimately true for private market valuations too. What will happen when your once-popular high-priced startup is inevitably weighed?

Growth flywheels can be powerful, but they take time to get going. When you raise at a higher valuation you are trading precious patience for money with diminishing utility while simultaneously raising the hurdle you must clear to raise your next round.

Raising at the highest possible valuation is the startup equivalent of buying more house than you can afford. You may be able to make the payments for a while, and you’ll enjoy a more comfortable lifestyle, but any minor shock could put you out on the street.

At a startup there is so much that is out of the founder’s control — Playing the long game and not inflating value in the short term is one of the few levers entrepreneurs can and should guard jealously.

In summary:

🎰 “Pricing to perfection” increases founder risk by increasing burn rates, shortening runway, decreasing investor patience & eliminating lucrative exit options.

😡 High valuations feel “founder-friendly” but actually create profound misalignment between entrepreneurs and investors that is only seen long after the “awesome” financing deal is closed.

How do you bootstrap a $1B+ hardware startup?

SimpliSafe founder Chad Laurans recently shared some wisdom with our portfolio:

🪤 Avoid the “trap of perpetual unreadiness”

🎯 Have a hiring “hit rate”

♻️ Start succession planning from day one

Here’s more…

🎯 Have a hiring “hit rate”

If you’re scaling quickly, you’re not going to hire perfectly. However, many managers fear losing face by admitting they made a bad hiring decision. Give them a permission structure to end poor fits before they poison your organization.

☑️ Reference people early

Chad urges hiring managers to call references as soon as they’re first excited about a candidate. Leaving calls until too late in the process leaves you susceptible to sunk cost biases and robs you of the ability to get insight on negative feedback.

🔐 Know thy market

The home security market has many attractive qualities, but few typical markers of VC-backed startups — No network effects, winner takes all dynamics, etc.

This meant Chad didn’t have to raise a ton of capital to compete in an effort to “get big fast.”

🪤 Avoid the “trap of perpetual unreadiness”

One of the hardest things to do as a founder is to ship a product that feels unfinished. However, it’ll almost never be truly “ready.”

Solve for the key value proposition and fix the rest in version 2.0.

🔽 Focus on the bottom of the funnel

In the earliest days, you are better off focusing on the lower portions of your marketing funnel.

Focus on getting more of the people who come to your site to convert rather than trying to get orders of magnitude more people to visit your site in the first place.

📞 Customer service > Consultants

Make your executive team answer customer service calls and probe online reviews before hiring expensive market research consultants.

Your best users are probably telling you what you need to know — and certainly what you need to fix.

🏠 Visit your customers

Users will find workarounds for shortcomings in your product that you could never imagine. Whether you sell SaaS or consumer goods, learn from your users where they live and work.

📢 Internal communication won’t scale itself

When Chad’s entire team was crammed in a single office it was easy to perpetuate the culture he envisioned. When the team grew to hundreds of staff, internal comms became a mission-critical project that had to be managed closely.

♻️ Start succession planning from day one

Everyone on the team should be preparing to pass something on — be it responsibility for the email newsletter, to the CEO chair. In order to foster a culture of advancement, people have to be prepared to let things go.

Founders, if I told you that you could:

🧱 Increase productivity

♻️ Reduce turnover

🤗 Build loyalty

All in 15 minutes a day, you might think I was peddling snake oil.

There’s actually an easy way to do it.

Show gratitude.

Your best people *are* being recruited.

They’re being offered better titles, better pay, and the rush of being courted.

If you’re not making them feel recognized and valued at your company, they will take one of these offers.

Don’t lose them to a lack of attention.

I understand why founders let this slip. They have urgent fires to put out. They feel put upon by VCs, customers, and even their own teams. These are all good reasons to make appreciation a process. Start by booking 15 min a day to thank people for the work they’re doing.

I mean this literally. Block 15 minutes on your calendar *every day* and use it to find ways to thank your team. Even a specific email thank you can make a huge difference and make someone’s day.

Just a few words can make an outsized impact:

“The new slide deck looks great!”

“Your analysis of the competitive landscape was insightful.”

“I’m glad you pushed back — you raised important points!”

“This new ad copy is hilarious, and it’s converting; keep going!”

You don’t need to compliment everyone. However, assuming you are decent at recruiting, 80% of folks at your company are probably doing good work — some even excellent work. How many regrettable losses are you willing to bear over the failure to make those people feel valued?

This practice will come naturally to some, but I find it doesn’t for most. If you’re the type who is reflexively uncomfortable with this idea, it is all the more important to set up a system to make up for this costly shortcoming.

You may balk at the idea of scheduling something that should be heartfelt. Most founders will find that it soon becomes an organic habit after they make time to do this programmatically. If you focus on making the comments heartfelt, that will come through.

“Programmatic appreciation” can work wonders. It becomes contagious. When senior managers see the CEO express appreciation, they do the same. At some point, the inevitable outcome is a company with a positive culture where employees feel valued.

For those founders reading this and rolling their eyes, here’s a different frame: your employees are all working hard trying to make you a billionaire. It shouldn’t be hard to appreciate that hard work and find daily reasons to offer gratitude.

These small gestures take minutes and cost quite a bit less than a retained search to find a replacement for a single regrettable loss or the raise that you give someone to keep them at the company when they got a 50% higher offer elsewhere after feeling undervalued.

Raises, bonuses, and stock options signal appreciation in a material way, but don’t underestimate the ROI on a small act of kindness!

Capital First Companies

November 20, 2020

🤖 Product-first companies are inspired by a breakthrough in technology or UX.

Awesome!

📈 Market-first startups are built in response to glaring inefficiencies.

Awesome!

🤑 Capital-first startups are catalyzed around access to capital.

Beware!

Capital-first startups start with a hazy sense of a problem, a rough idea about how a product could solve it, and a crystal clear conception of why they should raise maximum money, now, and at the highest possible valuation.

Spotting these startups is easy:

🏀 They build teams before they’ve tested a hypothesis

🏙️ Space is leased before wireframes are crafted

📜 Press releases are issued before customer personas are fully baked

📢 Buzz campaigns are ramped before any sales

This approach is seemingly enviable!

The founders who can pull this off have often had early-career success. They’re enmeshed in networks that make connecting capital easy. Crafting compelling pitches to suit the themes of the day is second nature.

I say this is “seemingly enviable” because building your startup on your ability to attract capital is dangerous. This approach allows founders to get out of the gates quickly while almost certainly spelling their doom.

Here’s how:

🔥 The Burn Rate is Too Damn High!

In the earliest days of your company, time, not money, is likely to be the gating resource. It takes time to understand the market. Iterating on the product requires cycles. Testing channels and price discovery can take a while.

It’s much easier to undertake these projects with a skeleton crew. But the dynamics of the typical capital-first startup won’t allow for that. They hire rapidly to try and solve these problems in parallel and live up to lofty capital infused expectations.

This rarely works.

💣 Pressure Mounts!

Capital first companies start with high valuations paired with high burn rates. This removes any margin of error and leads founders to chase vanity metrics over value creation. And to be fair, this can work for a time!

But it only works as long as you can keep your investors excited. Invariably, their enthusiasm will run out, and you’ll be left with the husk of a company.

These startups end up saddled with debt from short-sighted product/hiring decisions that were made in order to juice short-term growth…and no understanding of how to grow organically.

More importantly, the promising concept at the core of your business will be wasted. There are cases and classes of entrepreneurs that do need capital early in their lives in order to get started, but that is seldom the case in these scenarios.

In many of these scenarios, the founders I’ve talked to have the financial capacity to get started without investment or a tiny pre-seed, but the status that comes with venture dollars and the attendant perks — team, offices, etc. — is too tempting to pass up.

🥦 The solution is simple but unattractive

I sometimes worry I sound like a doctor telling people to eat their broccoli. Unfortunately, I don’t have a flashier message. When it comes to building companies that last, there is no school like the old school.

Capital can’t find your market, identify real problems, forge deep solutions, and create lasting value. Abundant capital is a multiplier when you have these things and compounds negative value when you don’t. Remember, capital has no insights!

Confidence: The currency of acceleration

August 13, 2019

Imagine you’re a billionaire starting a new company. You’re happy to bet your entire fortune on it. As a result, capital is no constraint. How fast should you burn money?

You probably wouldn’t use the generic startup math of dividing your available capital by 18 months and burn $55.5 million a month — though it would be fun. So if capital is no longer the currency that determines how fast you go, what should?

It’s confidence, not capital, that should be the currency of acceleration at a startup — no matter if you have a million dollars or a billion dollars to burn.

Confidence is often misunderstood by those who feign it. It is not bluster or arrogance. It’s not “trusting your gut.” Competitors raising big rounds of funding shouldn’t change your level of confidence one way or the other unless they’re doing exactly what you are. Glowing press coverage helps team morale, but it shouldn’t color your assessment of readiness to scale up.

It’s also important to note that venture capital interest is a terrible proxy for founder confidence. VCs have different structural incentives than founders; in an easy money environment, placing a big bet in a hot category, backed by a good enough team, is a job well done for a VC. Remember that they have a portfolio of companies; you’ve just got the one.

So what should drive you to scale up spend? There’s no perfect answer, but if you consistently see strong customer response to your product, marketing delivering more qualified leads for less money, sales channels becoming better instrumented and more efficient, LTV expanding with product improvements and lower churn thanks to your customer success team, you’re probably in good position to accelerate investment.

Too many startups feel pressure to spend money based on hope, not confidence.

Compounding successes at all levels of the business should provide data points that give you the determination to plan out a more ambitious trajectory. The requirement for confidence shouldn’t be mistaken for conservatism. Startups need to take risks in order to thrive, but they should be calculated, not capricious. There is a limited speed any company should go based on what they’ve learned to date about their market and offering.

If you have a high degree of confidence that you can turn $1 into $2, or $10, you should invest immediately. If you don’t have that confidence, you should spend time, but limited capital, to build it. Unfortunately, too many startups feel pressure to spend money based on hope, not confidence.

Authentic growth

Startups appreciate in value through growth. This isn’t just another VC mantra: even bootstrapped startups or public companies become more valuable when they grow faster. Two $10 million companies where one is growing at 80% and the other 20% will be valued very differently. Even if the slower-growth company is generating some limited cash flow and the high-growth company is burning within reason, the high-growth company will usually be worth much more.

So given that growth drives value, why shouldn’t every startup grow as quickly as it possibly can? With capital in hand, why not spend to generate more growth and therefore more value?

Capital without confidence shouldn’t dictate a startup’s acceleration.

Shattered confidence kills startups

Companies that misuse capital as the driver of acceleration cause irreparable harm to confidence. When a company over-accelerates and misses, it takes a painful amount of time to observe the mistake, admit the mistake, correct the mistake and rebuild confidence with the team and investors that you won’t repeat the mistake. Eventually, the company must undertake the inevitable process of taking a huge step back to try to rebuild that faith. This requires going much slower than a similar company that has never faltered.

If you spend a small amount of money on a pilot and it fails, you’ve helped home in on what your product should be, and you’ve not burnt any credibility with your team or investors. Spend 10 times that amount and you’ll have no more confidence in what to do next, far less credibility and a diminished balance sheet. Worst yet, the next time you want to lean in on a major initiative, the lack of confidence of key stakeholders will likely overwhelm what may well be the right decision.

Three startup currencies: Confidence, credibility and capital

Companies create value by compounding learning and therefore compounding confidence in their future. As confidence grows, companies will earn credibility inside the management team and with investors. Once you have both, it usually gets easier and easier to find the right amount of capital needed to fuel that confidence. Confidence is the most important currency, followed closely by credibility, and only then, cash. By way of contrast, driving up revenue artificially by burning capital with low return on investment is not sustainable and does not create long-term value. This will ultimately damage confidence and credibility.

You can buy confidence with capital, but it’s rate-limited and there’s no benefit to scale

Arguably, there should be little difference between the acceleration of two competitive companies that have the same amount of confidence but radically different capitalizations. If both are early-stage startups and one company has $10 million in cash and the other has $1 billion, they should spend their money with the same principle in mind: what does it cost to build confidence that our most important experiments are working?

Authentic confidence is the only real winning weapon at a startup.

For a company with a million dollars, this may mean hiring a single inside sales rep to test out a direct channel based on some early successes with a specific type of customer. A company with a billion dollars will likely make the mistake to open global offices to meet international demand, without first validating that they can make that single inside sales rep successful. In both cases, the confidence of the management team and their ability to execute should be driving the decision, not the available capital.

Credibility is earned, not purchased

If you spend like you’re headed to $20 million ARR and only hit $10 million ARR, your business is in a very difficult position. Not only because you sustained large losses, but also because you’ve damaged confidence in execution — team members and investors won’t believe in the company’s ability to achieve the target the next time it wants to hit the gas pedal hard.

Conversely, If you confidently hit $10 million in sales and have sight lines to $20 million, you will not struggle to raise more money to achieve your goals. The more the management team meets its goals, the more confidence grows and the pace of acceleration can be increased. Compound confidence, and acceleration is boundless.

One of the biggest mistakes of the startup community, fueled by an overcapitalized venture market and an overhyped argument about winner takes all market dynamics, is the belief that capital is a weapon that will win the startup wars.

Authentic confidence is the only real winning weapon at a startup. Capital can fuel that weapon, but when used without confidence, it usually becomes a weapon of self-destruction.

Redefining dilution

July 20, 2018

Everyone generally agrees that dilution should be avoided. VCs insist on pro-rata rights to avoid the dreaded “D” word. Executives often complain, after a new financing, that they should be “made whole” to offset the dilution that came with the new round. Founders work as hard as they can to maximize their valuation at each financing event to avoid painful dilution. Dilution = bad.

And yet, entrepreneurs want to raise money. In many cases, they want to raise lots of money. There is great pride in the amount of money that is raised and a larger raise is typically celebrated as a greater success. This is a bit confusing, given that a larger raise should also mean more of that awful dilution that everyone is trying to avoid.

Financing events are misleading

Most people in the startup ecosystem think of dilution as the percent of the company that is sold in a financing transaction. If your startup completed a $5 million Series A on a $20 million pre-money valuation, (option pool aside) you would have 20 percent dilution, and everyone will own 20 percent less than they did before the transaction. This is very misleading.

While every equity holder may own 20 percent less of the company than the day before the financing, the company is worth more than the day before the financing. Even if you assume that the valuation was an objective measure of the value of the company and was flat from the previous financing, everyone now also owns their percentage share of the new cash that was added to the cap table, which wasn’t part of the company’s value prior to the financing. Here’s an example:

| Company Value | Your Ownership | Your Dollar Value | |

| Pre-Series A | $20M | 10% | $2M |

| Post-Series A | $25M | 8% | $2M |

So if you owned 10 percent of the company, and the day before the financing that was worth $2 million, the day after the financing you own 8 percent of the company, which is still $2 million. In dollar value, which should be the only value that economically matters, you own the exact same amount of a company that is now worth more overall. Where is the dilution?

Financings are usually accretive, not dilutive

I believe the startup ecosystem is confused about the impact of financings. Rather than being dilutive, any up-round financing (with a caveat that I’ll address below) should be a demonstration of value accretion. Let’s add some context to our previous example.

If the previous round had $10 million post-money valuation, and you owned 10 percent, your ownership was worth $1 million at the time of the seed financing. With this new $5 million financing on a $20 million pre-money valuation, you may now only own 8 percent of the company, but your value in the startup has actually doubled to $2 million. That’s amazing!

| Company Value | Your Ownership | Your Dollar Value | |

| Post-Seed | $10M | 10% | $1M |

| Post-Series A | $25M | 8% | $2M |

Why would anyone focus on the 2 percent reduction in percentage ownership when the value of their holding appreciated from $1 million to $2 million? It’s always better to own less of something worth much more than own more of something worth much less. That’s a trade I’d make every day of the week, and it isn’t at all dilutive to my ownership. Complaining about dilution on that transaction is totally illogical. We should all be celebrating the accretion of value when we have an up-round financing.

If VCs want to purchase their pro-rata because they believe in the long-term value of the startup, and buying pro-rata is part of their strategy, by all means, they should do so. However, if they are doing so to avoid dilution, I think they’re missing the point completely, given that they haven’t been diluted. If a founder receives more stock options because their performance is outstanding and they deserve more compensation, that’s terrific. If they are being “made whole” because they own a smaller percentage, which has doubled in value over the larger percentage they previously owned, that’s simply faulty math.

True dilution = burn rate – accretion of value

While financings reflect value accretion or dilution, the transaction isn’t where these values really change. Dilution is actually much more complicated and shouldn’t be viewed as a transactional event.

Dilution is a function of your burn rate relative to your accretion of value. It is often measured in financing events, but it actually plays out every day in the choices the startup makes and the work the startup accomplishes. Simply put, if you are accreting more value than you burn, there is no dilution. If you’re burning more cash than you’re accreting value, then there is dilution.

Put another way, you’re not being diluted because a VC decrees it; you’re being diluted because you spent money building features that your customers didn’t want, instead of the ones that they need. You’re being diluted because you kept scaling up an ineffective sales process because you didn’t want growth to slow.

Each financing event is more of a check-in point on the value of the company than a true dilutive or accretive event. It’s the time between the financings, when the company was burning cash to build additional value, that was truly the accretive or dilutive journey. In other words, the company isn’t worth $20 million because someone bought stock in a day. Its valuation increased from $10 million to $20 million because of the work that was done to increase the value of the company that greatly outpaced the cost of creating that value. If the cost outpaced the value of the work, that would have been dilutive, as demonstrated by a down round.

The paradox of overvalued financings

It’s the burn rate relative to the value creation, not the financing event, that truly determines accretion or dilution. However, I’d acknowledge that this equation is ambiguous at all times and the market determines that value, which is why it is fair to say that financing events are the measuring moment of the most recent period of work.

What’s particularly complicated is that financing events are incredibly inaccurate measures of value creation.

In the recent era of an overcapitalized venture capital industry, we’ve seen some extraordinary financing events across nearly every startup stage. So what is the implication of overcapitalized and overvalued companies? Are those transactions clear evidence of value accretion?

Unfortunately, this is a particularly confusing phenomenon. These financings are celebrated because they appear to be minimally dilutive and the company gets a stock-pile of cash. Unfortunately, I think they distort the economic equation of the startup and usually have the opposite result.

Imagine that same startup that rationally should have raised $5 million on $20 million pre-money is able to raise $20 million on $80 million pre-money.

| Company Value | Your Ownership | Your Dollar Value | |

| Post Seed | $10M | 10% | $1M |

| Post Series A | $80M | 8% | $8M |

This type of round seems crazy to anyone who hasn’t experienced it, but we’ve been there with our companies many times. It appears that the company has just had an exceptional outcome. The person who previously owned 10 percent still owns 8 percent, but the value appears to have increased from $1 million to $8 million. Happy days! For the same 20 percent dilution, the company raised 4X the capital and stock is now worth 8X the last round value! Unfortunately, it is the embedded future implications of this event that are so misleading and undermine that value.

Because it is the burn rate and not the transaction that really drives dilution, typically these large financings end up being very dilutive to the company. As I’ve written about previously, these financings often come with unreasonable pressures to prematurely grow the business and incentives to chase the marginal dollar at great cost. The end result of these financings is typically that the burn rate will often outpace value accretion at the startup. This is extremely dilutive over time and typically will have the effect of conditioning a company for an indefinitely high burn rate, which will require much more cash and possibly a down round in the future. Or worse yet, the company fails as the investors lose enthusiasm and the company is depending on continued cash infusions that never come.

In other words, large financings are typically very dilutive, even if on paper they appear to be evidence of massive value accretion and misleadingly little dilution. Paradoxically, given the same stage of growth, the $5 million financing for 20 percent of the company is often more likely to be long-term accretive than the $20 million financing for 20 percent.

Words of caution

I would encourage startup founders, employees and investors to stop viewing up-round financings as dilutive and recognize that they are accretive (except when they incentivize future wasteful spend). Instead, they should obsess about the burn rate and ensure that the capital being burned is invested in high-confidence opportunities that yield true value that will be reflected in accretive future financings. If every dollar invested is showing demonstrable value accretion, by all means burn as fast as confidence allows! Profitability is important, but focusing on it too early can undermine value in the same way that burning too aggressively can. The point of venture capital is to make investments in confident areas of high growth. Venture capital is not the right tool for every job, but if a startup can use VC as intended, they should.

We had a saying at my last startup that “every dollar that we spend is a dollar of dilution.” While that was probably a good mindset, the wording suggests that investing in a business with strong return isn’t worthwhile. Today I’d revise that saying to “every dollar that we spend that doesn’t create more than a dollar of value, is dilution.”

May your burn rates be accretive and your financings increase your ownership value.

When venture capital becomes vanity capital

March 5, 2018

I’ve written a lot about the benefits of efficient entrepreneurship. I’ve explained my view conceptually, tried to illustrate the mechanics of how excess capital kills promising companies, and shared data from 71 IPOs that demonstrates that even in success, more capital raised is not correlated with better outcomes. Just in case all of that was too conceptual, this blog post is designed to appeal to another emotion—greed.

Raising less money or money later doesn’t just lead to better companies, it leads to richer founders.

Would You Rather Be the Founder of Zappos or Wayfair?

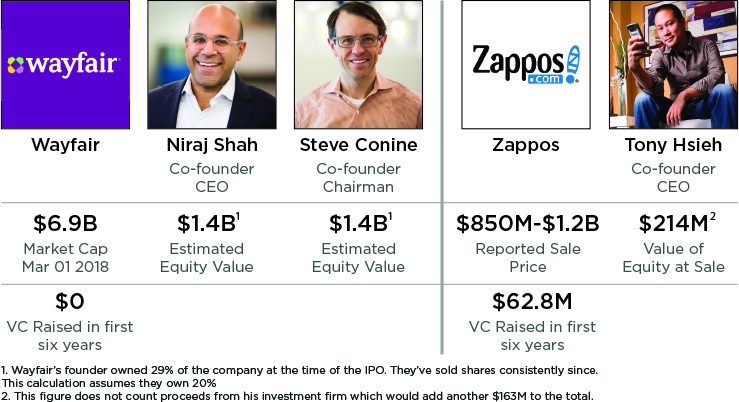

I regularly ask MBA students at Harvard Business School, by a show of hands, would they have rather founded Zappos or Wayfair? All of the students know Zappos as a success story. Many haven’t even heard of Wayfair. Nine out of 10 of these savvy students choose Zappos.

Zappos is a textbook success story. They raised staged, smart money from the best VCs in Silicon Valley. Founder Tony Hsieh’s unorthodox approach to leadership earned him magazine covers and a book deal. When the company was purchased by Amazon for somewhere between $850M and $1.2B, Hsieh walked away with somewhere between $214-367M. This is an extraordinary sum – a great success that makes Zappos a model that founders should study.

But there are even better ecommerce startup stories that few founders know to study.

Contrast Zappos with Wayfair, an ecommerce company that dropships furniture. The founders, Niraj Shah and Steve Conine bootstrapped the business and grew rapidly by optimizing against Google’s algorithm, buying up hundreds of SEO friendly URLs like “www.racksandstands.com” and agglomerating the traffic. The company was profitable from the first month and, despite many VC offers, they grew the business without outside capital until they had over $500M in sales. Some might view the company as solid, stable, and a little bit boring, but the founders were laughing all the way to their IPO on the NYSE in 2014. Among numerous remarkable attributes about the company is the financial success of the founders.

Each of the founders owned ~29% of the company at the time of the IPO. Though they’ve regularly sold shares since, based on the company’s current $6.9B market cap, EACH ONE of Wayfair’s two co-founders made as much money as ALL of Zappos’ shareholders combined. Put another way, by building an exceptionally capital efficient business and only raising money when the company was already very valuable, each Wayfair co-founder made nearly 10X as much as Hsieh. I’d rather be Shah and Conine.

Minimize Capital Early

You might say this discrepancy has to do with the relative size of the furniture and shoe markets. To be fair, the furniture business is approximately twice as large as the footwear market, though the shoe industry is arguably a better fit for ecommerce given the repeat nature of the customers, lower shipping costs, and much less friction for trial and return.

While the industry dynamics likely play a role, I believe it’s the company’s capital strategies that made the difference. Wayfair didn’t raise money to start the company or to accelerate early growth, though it would have been easily available along the way; they only raised money when it was time to dramatically expand their business and invest in an already large and healthy company. They weren’t shy about taking on massive amounts of capital: Wayfair raised three times the capital that Zappos did, but only when it was minimally dilutive, after the company’s dominance was established, and could provide massive amounts of scale leverage.

It’s Not All About the Benjamins

Taking capital too soon, and with too much dilution, has ripple effects beyond eventual payouts. After selling to Amazon, Hsieh suggested he was “forced” to sell the company due to pressure from his shareholders. Everyone involved made a fortune, but it is frustrating to subordinate your preferences based on financing decisions made half a decade earlier. If left in control of Zappos, Hsieh likely could have continued to grow his company and possibly even matched Wayfair’s success. The Wayfair founders owning more than half the company even at the IPO, and having raised money on their terms with limited dilution, were able to control their own destiny to a much greater degree and still run a phenomenal business today.

TrueCar vs. CarGurus

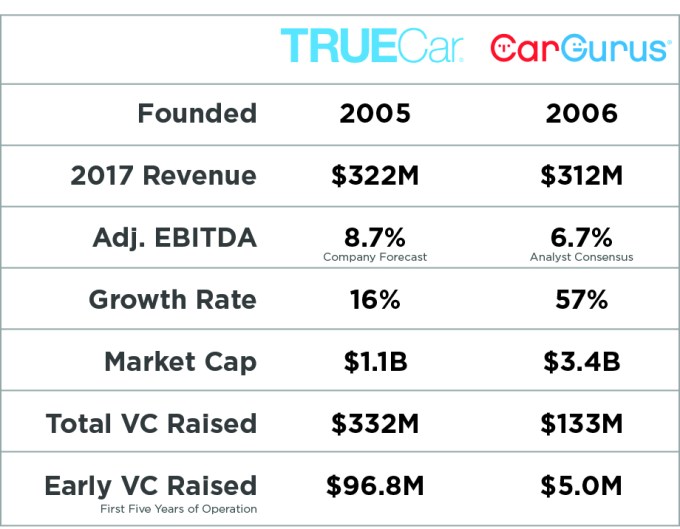

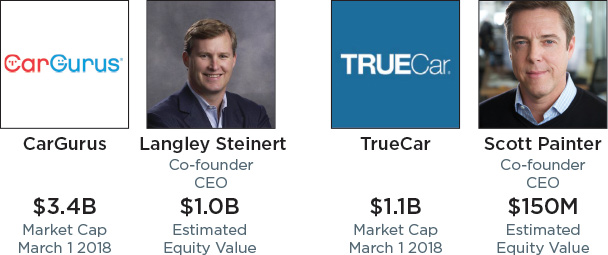

Let’s start again: by a show of hands, which public auto ecommerce company would you rather be – The founder of TrueCar or CarGurus? Decide before you look at the table below:

That’s right, with much less capital raised, CarGurus is similarly profitable and growing much faster than TrueCar and therefore worth more than three times as much.

Because of the light capitalization of CarGurus, Langley Steinart owned 29% of the company at the time of its IPO, a stake worth close to the entire value of TrueCar. At the time of the IPO, TrueCar founder Scott Painter owned ~14% of his company, an extraordinary amount to be sure, but this represents just a tenth of Steinert’s total value in CarGurus.

Even in success, more capital does not make for better businesses, and raising less money can pay off in multiples of personal wealth and control.

These Are The Great Outcomes

In each of these examples, both companies succeeded and founders benefited with exceptional financial success. When I pose these thought experiments to entrepreneurs, they often push back and say that they’re willing to take less personal financial gain for the chance to build a well-known brand. They’re willing to forgo a billion-dollar bank account in favor of a mere hundred-million-dollar payday and fame. The reality is that this is rarely the tradeoff offered to founders.

The more common exit opportunity is not a multi-billion dollar IPO, but a $50M-$100M acquisition. If you’ve raised a modest amount of money, that can be a transformative outcome. If you’ve raised tens of millions of dollars (or sometimes hundreds), many, if not all, of those exit opportunities will be closed. The high-probability choice that overcapitalized companies face is a decision to take $50M and fail to clear your venture investor preference stack, or face bankruptcy and lay off your entire team. In either case, there is a good chance the founders see little or no return.

A decade after their formation, Wayfair and CarGurus have become more valuable businesses than their counterparts, and the founders benefited greatly from their lean financing strategies, but they’ve had something even more valuable along the way—optionality.

Because they were never beholden to venture capitalists or outsize valuations, they had the flexibility to sell for $50M or $500M along the way. These founders could decide to sell, or not, depending on the performance of their businesses and appetite for risk, not their capital structure. There’s no shame in a $100M startup and founders shouldn’t be so quick to concede that option along the way.

Even in success, too much capital has a high cost and shouldn’t be underestimated. Likewise, efficient entrepreneurship has many benefits that shouldn’t be underestimated. Just ask Niraj Shah, Steve Conine and Langley Steinert.

The plague of rationalization

February 15, 2018

There are many reasons startups fail.

Unfortunately, we just didn’t have enough time and ran out of money.

Unfortunately, the customers just didn’t care enough about our offering.

Unfortunately, the channel just wasn’t economically efficient.

Unfortunately, I had the wrong person running engineering (or marketing, sales, finance etc.).

Unfortunately, we were screwed anyway so we just decided to throw a Hail Mary pass.

Unfortunately, I thought layoffs would ruin morale, so we just burned too much for too long.

Unfortunately, the term sheet fell through at the last minute and we ran out of money.

Unfortunately, we didn’t land the key account that would have saved the business.

Unfortunately, because we had always overcome every previous obstacle, we blindly assumed we’d always overcome the next one.

These are just a small sample of the explanations I’ve heard as an investor, usually immediately after the company runs out of money.

There are times a startup’s fate is beyond its control. Like when a platform tells you they’ve unilaterally decided to take your revenue streams, or a country bans your app. However, outside of a few rare circumstances, the life or death of a startup is mostly in the founder’s hands.

Startups don’t just “run out of money.” Instead, they wait too long to address problems while they had money. Failure doesn’t usually happen “to” startups. It happens when founders rationalize problems until it’s too late and put off dealing with their most profound challenges.

Most of the problems above are present at some point, not just in failures, but also in every successful company. The difference between success or failure is how quickly the startup engages the problem. Attack problems early and the startup will advance. Rationalize that the problems don’t exist and you’ll just be another depressing startup post-mortem.

Why we rationalize

Founders are amazing at bending the world to their will. They succeed partially because they can see what’s possible before most people and have enviable imaginations that can design the future. While this can be a strength, it also can be a great vulnerability.

A successful founder must manage the paradox that they are both inventing the future and that the future is in no way inevitable. Just because a founder wants something to be true, doesn’t mean it will be. And just because the founder has been proven right before (“30 VCs said no to us before we closed our Series A…”), doesn’t mean that founder will be right again (“…therefore we just need to persist through all this rejection to get to our Series B”).

Rationalization is a plague that stands in the way of aggressively removing the barriers that will prevent success.

Founders need to have their eyes to the sky and their feet planted firmly on the ground. They need to at once imagine a future and aggressively study the reality of how the world (customers, employees, recruits, investors) is responding to that vision. Unfortunately, being visionary can easily seduce founders to rationalize away reality.

Identifying rationalization

The best way to detect rationalization is to figure out whether a founder is earnestly searching for answers to problems or is quick to explain away why the problems aren’t important.

Rationalizing founders will use the “Five Whys” to figure out why a negative piece of data doesn’t apply to their startup. The wise founder will try to figure out how to adjust to the learnings.

When introduced to someone with deep domain or functional expertise, the rationalizing founder puts off talking to the person and argues why the person’s input isn’t relevant. The earnest founder eagerly sets up the meeting. That founder may not agree with this person’s perspective, but is openly mining the expert for information. Why did another company in the space make the decision it did? Who are the three best people to talk to about problem X? Good CEOs are always on the hunt for people who may have insights that can help their company overcome barriers.

Rationalizing founders have a tendency to mock a competitor’s approach to a problem — even if that competitor is having much greater success! A truth-focused founder seeks out the competitor’s customers and tries to find out why they are doing so well.

The misaligned incentives of the venture industry also contribute to the likelihood of founder rationalizations. Companies with respectable linear growth stories that want to raise venture capital often rationalize why they need to invest aggressively in their businesses to drive an exponential curve, even when they have limited evidence to support the probability of that curve. By doing so, these founders disregard the data in front of them and start down a path of rationalization that is hard to unwind.

Attack the problems

It’s tempting to blame external factors for the failure of a startup, but success or failure almost always comes down to decisions that the founder makes, or chooses not to. Every startup faces huge challenges on the road to success. The speed with which startups address (and even anticipate) these challenges dictates the outcome. Rationalization is a plague that stands in the way of aggressively removing the barriers that will prevent success. Most founders only realize they were rationalizing when they’ve run out of time, and it’s too late.

Learning to embrace conflict as a part of startup culture

December 17, 2017

A startup is a journey of questions with as yet unidentified answers. Most startups fail because they never find true enough answers to succeed. Startups succeed when the founders are focused on finding the truest answers to their most important problems.

What is the best way to engineer a product that will delight customers? What is the most efficient channel to get that product into your customers’ hands? What is the most effective way to scale up that model to maximize the impact and commercial success of the business? Who are the right leaders to help achieve these goals? Even small questions seek “truth” – What color button on a website is most likely to convert the customer?

While there isn’t a single “truth” that is the correct answer to any of these questions – each fork in the road has more and less true answers. The job of the founder and leadership team is to find the truest path to success. Unlike large companies operating at scale, at a startup the unknowns are overwhelming, and data cannot by itself resolve most of these decisions.

Most team leaders will agree on the majority of decisions that need to be made, and good startup teams seem telepathic at times, but there are inevitably going to be profound disagreements. It’s critical that entrepreneurs embrace these conflicts because solving them properly is often the difference between success and failure.

If the decisions were easy, someone would have made them already. The conflict exists because the answers aren’t obvious. It’s in the conflict that the right answers emerge. You have to lean into the conflict to win.

Conflict Failure Modes

Avoiding the Conflict

I believe the most common conflict failure mode at a startup is when the leadership disagrees on what should happen, but no one speaks up because it’s uncomfortable to do so. The team is in full denial that there is even disagreement on the hard choices that need to be made. As a result, these choices aren’t made at all, and the leadership of the company makes the wrong decisions while pretending that everything is okay. Inevitably, after the company fails, leadership team members lament that they knew that the company was going in the wrong direction and should have spoken up sooner. Yes, they should have.

Ego

Ego makes conflict painful because we try to avoid hurting others’ feelings while protecting our own. But for many, winning the argument becomes more important than the company making the right decision. Therefore, when we engage conflict, we become emotional and want to win for ourselves, confusing this emotion with our desire to win collectively. While each of us struggles with this tension, the problem is exacerbated by the fact that everyone in the debate naturally is subjective on the superior value of their perspective. This tendency can often lead to anger, insecurity, and unnecessary emotion that makes conflict painful, relationship-threatening and unproductive. Unfortunately, ego frightens many team members to shift into conflict avoidance.

Strong Personalities vs. Wall Flowers

Often in ego-driven conflict, stronger personalities will win despite having no greater insight on the truth. It is crucial for a company to make sure that conflict is not resolved simply by the strength of personality. Otherwise, the company will have a scenario where personal victory – “I need to be right” – comes before company victory – “we need to be right.” The wallflowers have no less claim on the truth of their market, operation, or product. They often just have less eagerness to fight.

Softening The Edges

In polite conversation with friends and relatives, we are all taught to soften the edges of our conflict. In other words, we pretend that we mostly agree, even when we don’t. This adaptive approach to conflict at least arguably makes sense in a social setting. We can politely agree to disagree largely because in social settings we don’t have to collaborate to make critical decisions. At startups, softening the edges can be catastrophic. It causes leaders to work in opposite directions or procrastinate making the hard decisions.

Revert to Mean

Empathy is often misapplied in a startup context. It’s great to embrace the idea that everyone’s opinion counts, but critical to understand that these opinions do not yield equally correct outcomes. The inability to decisively move forward, and instead find a middle ground on each topic, leads to Frankenstein solutions that rarely yield the correct answer. In this way, the startup prioritizes compromise over finding truth. If there is always a more true answer and team members are in conflict on what that answer is, there is little probability that the compromise answer is the right one. While everyone might feel good that their point of view was persuasive to a consensus outcome, they will feel much worse when they realize that compromise and truth have little in common at a startup.

How to Embrace Conflict

It’s easy to say that a company should embrace conflict and far harder to do so successfully. Ultimately, engaging conflict is among the most significant cultural challenges for startups, but also among the most important.

Reframe Conflict As The Search for Truth

Most people don’t think about a startup as a search for truth. It’s important to frame the quest of the startup this way and make sure that everyone understands that the purpose of a startup is experiment constantly in the service of finding the best answer to pressing problems. Everyone has the right to question the assumptions, and no one has a monopoly on being correct – yet in aggregate the company making the right decisions will make or break its success.

Call out Objectivity and Subjectivity

Companies need to build a culture where it is okay to question whether a colleague is being fully objective. By acknowledging the natural human tendency toward ego, it should become okay to check with colleagues whether their judgment is being clouded by their own need to win the argument, versus their desire to find the right answer. By being willing to engage in this type of self-reflection and giving others the license to question you, egos can be moderated.

Be Hard on Problems, Not People

Remind everyone that it is the problem, not the people, that should be the focus of the conflict. When team members start to attribute negative intentions and motives to their colleagues, it becomes very difficult to put ego aside and focus on finding the right answer. By being soft on people and hard on problems, the company can build trust as the basis for the exercise of doing the hard work of making decisions collectively, rather than playing the ego game.

While maintaining empathy for individuals, the culture shouldn’t have empathy for ideas. The best ideas can come from anywhere in the organization, from the CEO to the most junior team members, and everyone should be speaking truth to power at a startup. Having said that, everyone must accept that not all ideas are equal. Being respectful of everyone’s contributions is often confused with valuing all ideas as equally likely to be truth. Every single idea has a relative truth value to all others and must face that crucible.

Debate, Don’t Fight

Ego turns conflict into a fight. The goal is to avoid the fight, but engage the debate. Try to be objective and curious about others’ points of view. Listen to each other and work toward finding the truth. Keep debating until you find it and work hard to parse differences in assumptions and beliefs. The challenge is to build a culture where team members work as hard as possible to defuse the fight by showing enthusiasm for the debate.

Hard decisions take time and deserve intense debate, but when debate becomes a fight, it’s time to take a break and calm the negative energy. When taking a break, always address when the debate will continue, or breaks can often slip into conflict avoidance.

Gauge Magnitude of Beliefs

Some people just like to argue for the intellectual value, even if they don’t feel strongly about a particular outcome. Others are stubborn and don’t like to lose arguments, on principle. Both of these instincts must be subordinated. However, there is often truth in the magnitude an individual feels about an issue. Those who are effective at subverting their egos, but feel very strongly on a hypothesis, often have strong insights powering the magnitude of their belief. It’s important to listen to those who feel most strongly – particularly when they are not the strongest personalities at the table.

Consider Hierarchy & Roles

On teams where debate becomes unproductive, drawing lines around areas of responsibility can help. Deference to greater experience, domain knowledge, or responsibility for the outcome are all reasonable solutions for many debates. Let anyone add to the debate, but in many cases it is best to leave the decision to the responsible party. Note that this approach can be risky—if an individual pulls rank too often and he’ll find himself without a partner or team, and will often lose credibility in the next debate.

At Some Point, The Debate Must End

Truly convincing or being convinced of the best decision for the company is the optimal path to resolve a conflict, but it is not the only way. Sometimes a team has sincerely delved into the differences as much as possible and is running out of time to make a decision. In those cases, the company must find a way to pick a direction and move forward as one. Constant dissent on the decision, once made, can be as problematic as not engaging the conflict in the first place. After the decision has been made, the company needs the benefit of a single team moving forward together.

Get Out Of The Way

When a decision is made, everyone must lock arms and move forward or simply get out of the way. We’ve seen many circumstances where talented team members needed to part ways after a high-quality debate, because they simply couldn’t agree on how to move forward. Sometimes startup leaders must accept that if they aren’t part of the solution, they are part of the problem.

You’re Paid For Your Opinion

I had a boss who frequently repeated the statement, “you’re paid for your opinion.” He was encouraging energetic debate by trying to draw out the wallflowers and build a culture where the stronger personalities learned to listen. Crafting this type of culture is the key to a successful team. Studies have shown the difference between good marriages and bad ones isn’t the lack of fights, but learning how to fight productively. This is also true for startup teams.

A CEO who believes he is always right, and rams decision making through an organization, will create a culture of people who feel frustrated, suppressed, and will regularly make poor decisions. A CEO who integrates dissent and healthy debate into the company will be primed for success and likely find the truth she is seeking.